March is Women's History Month! Dayton has had some pretty amazing women live, lead, and leave their legacies behind. Continue reading to learn more about a sampling of Dayton women who made history!

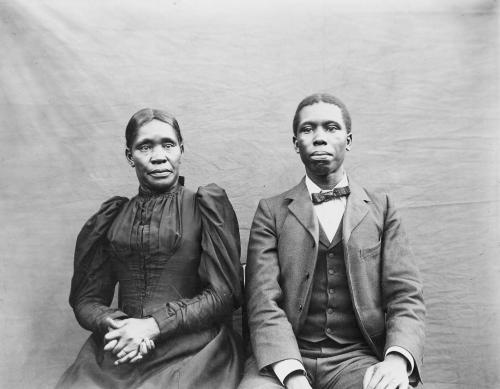

Erma Bombeck

Erma Bombeck, born Erma Louise Fiste, attended the University of Dayton, graduating with a degree in English in 1949. A regular contributor of humorous columns to school publications during both junior high and high school, she worked for the Dayton Herald during her years at Dayton Co-Op High School. While at the Herald, Bombeck interviewed a teenage Shirley Temple when she visited Dayton to promote a movie. The article won Erma a newspaper staff award and boosted her confidence in her writing ability.

Writing was a central part of Bombeck’s life - as a vocation and in order to help pay for her college classes. She wrote humorous articles for a company newsletter as a part-time job with Rike’s, the local department store. Eventually, Bombeck wrote for the University of Dayton’s student magazine publication, The Exponent and for the student newspaper, the UD News.

Bombeck left a lasting legacy, not only to UD, but to the larger community. Achieving success as a newspaper columnist, Bombeck provided humorous affirmation to housewives. She also wrote for magazines, including Good Housekeeping and Reader’s Digest and published eleven books during her career. In 1975, Erma began providing commentaries to Good Morning America and continued this through the mid-1980s. Bombeck wrote and produced her own sitcom, Maggie, a show based on her family life. (Credit: information taken from UD)

Jeraldyne Blunden

Jeraldyne Blunden was a choreographer, a dance instructor, and an artistic director.

In 1968, Blunden established the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company (DCDC), which developed from a small, regional African-American dance company to a nationally recognized one. In order to preserve a historic record of dance, she created, within the DCDC, a dance archive that includes a repertory of the masterworks of African-American choreographers. A choreographer herself, she regularly held workshops for young choreographers, giving them the rare opportunity to work with professional dancers. Blunden devoted her life to dance education and performance and provided inspiration for generations of talent. Her legacy continues today in Dayton's world-renowned DCDC. (Credit: Dayton.com)

Gypsy Queen (Matilda Joles Stanley)

Dayton’s Queen of the Gypsies is said to be buried at the “only sacred burying ground of gypsies in the United States,” according to the authors of the “History of Wayne Township, 1810-1976.” Before she ended up in the gypsies’ burial place in Woodland Cemetery, Matilda built a reputation as a fortune teller. Born in Reading, Berkshire, England in about 1821, Matilda was the wife of Levi Stanley, son of Richard “Owen” Stanley, king of a prominent gypsy tribe. Owen Stanley moved his affiliated families from England to the United States in 1856, according to a Dayton Daily News article. The tribe settled in the northern part of Dayton. They bought farms in Harrison, Mad River, Butler and Wayne townships to have houses to stay in during the cold months. Levi and Matilda’s reign as king and queen began when Owen and his wife Harriet died. (Credit: Dayton.com)

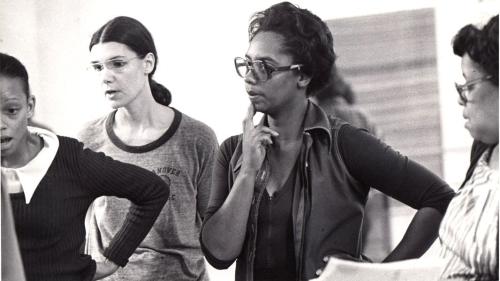

Matilda Dunbar

The mother of Paul Laurence Dunbar was born enslaved near Shelbyville, Kentucky, to Isaac Burton and Eliza Porter Burton. Her master, Shelbyville landowner David Glass, hired her out as a domestic servant until emancipation in 1865. He gave Matilda the opportunity to gain her freedom by immigrating to Liberia (West Africa), but slavery in the United States ended before her scheduled departure. Around the age of 16, amid the Civil War, she married R. Weeks (or Wilson or Willis) Murphy, who was also enslaved. Together they had two children, Robert and William Murphy. Matilda and R.W. Murphy separated after the war, with Matilda moving to Dayton, Ohio, to live with her mother in the spring of 1866.

In Dayton, Matilda worked as a launderer. There she met Joshua Dunbar, a plasterer. They married on December 24, 1871. Their marriage produced two children, Paul and Elizabeth Dunbar; Elizabeth died before her third birthday. As an enslaved child, Matilda had few educational opportunities. She wanted better for her children and attempted to show them the importance of education by enrolling in night classes at the tenth district school on Zieger Street while spending her days washing clothes, cooking, and sewing for Dayton residents. Matilda’s literacy was such that she taught Paul the basics of reading before he entered elementary school (though she did not teach her other sons).

Matilda’s life was connected closely with that of Paul. She and Paul rarely left each other’s presence; Matilda even moved to Washington, D.C., to live with him after his marriage to Alice Moore. After his separation from Alice in 1902, Matilda and Paul briefly moved to Chicago. In 1903, they returned to Dayton and, in 1904, purchased a house on North Summit Street on the city’s west side in a neighborhood that was overwhelmingly white. Paul wrote from this house until his death from tuberculosis in 1906. Matilda – commonly known as “Mother Dunbar” – lived in the Summit Street house, financially supported by relatives and neighbors, until her death on February 24, 1934. She is buried at Dayton’s Woodland Cemetery. Matilda gained a reputation as a gracious, well-spoken hostess who welcomed those interested in the writings of her son to her home. She maintained Paul’s library and study in their 1906 conditions and showed his work spaces to visitors. (Credit: Nps.gov)

Katharine Wright

The only surviving daughter of Milton and Susan Koerner Wright, Katharine was born in Dayton, Ohio, at the Wright residence on Hawthorne Street. The youngest of the Wright siblings (more than thirteen years younger than eldest brother Reuchlin), Katharine developed close relationships with the younger of the four brothers, Wilbur and Orville. With the death of Susan Wright in 1889, Katharine assumed much of the responsibility for managing the Wright household, especially during Milton's frequent absences. While Milton was rather demanding of Katharine in domestic matters, instructing her in household tasks in letters sent from across the United States, he did not want her to neglect her intellectual development. Katharine attended Dayton's Central High School and entered Oberlin College in 1893. She graduated from Oberlin with a bachelor's degree in 1898 and eventually obtained a job as a teacher of Latin and English at Dayton's Steele High School. Katharine taught there until 1908.

Katharine left teaching in September of 1908, after the crash of a Wright airplane piloted by Orville during a demonstration flight for the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia; a crash that killed Lt. Thomas Selfridge. She stayed with Orville during his convalescence, and after his recovery traveled with him to meet Wilbur in France for a promotional tour. Katharine actively assisted her brothers' careers, serving as a confidant and sounding board.

Katharine's relationship with Orville, who never married, became especially close after the deaths of Wilbur in 1912 and Milton in 1917. She served as a director of the Young Woman's League of Dayton, supported efforts to gain women the right to vote, and remained active in Oberlin College affairs, leading its alumni group and gaining election to its board of trustees. She also married a college friend, Kansas City newspaper owner and editor Henry J. Haskell, at Oberlin on November 20, 1926. While Lorin Wright heartily approved of the marriage, it ruptured Katharine's relationship with Orville, who believed that through it Katharine rejected him as a brother. He refused to interact with the couple, who lived in Kansas City, shunning Katharine until days before her death from pneumonia on March 3, 1929. Orville asked Henry to allow Katharine to be buried in Dayton, and she was interred with her parents and brother in Woodland Cemetery. (Credit: Nps.gov)